Diving among the largest mollusks on earth in the tropical waters of Yap

In the far western reaches of the Pacific Ocean, the small, remote island of Yap sits amid a rich coral habitat that is home to some of the largest sea creatures in the world.

Divers come to Yap from all over to swim with the resident population of manta rays that have a wingspan of up to 13 feet and weigh upwards of 1,500 pounds.

But giant clams with their scalloped, colorful lips, or mantles, turned upward from their permanent anchorage amid the coral, are also found in the warm waters of this far-off island.

Listed as “vulnerable” by marine conservation organizations, the clams are often among the sightings most treasured by visitors to Yap’s shores who plunge into the rich environment.

One of four island states in the Federated States of Micronesia, Yap is known to have one of the most well-preserved cultures in the entire region, and ocean conservation is an important part of the life of the Yapese who rely on sustainable aquaculture practices for their food supply and the economy.

In 2015, a community-managed network of Marine Protected Areas was formed by government agencies, non-government conservation and resource management groups, and community members.

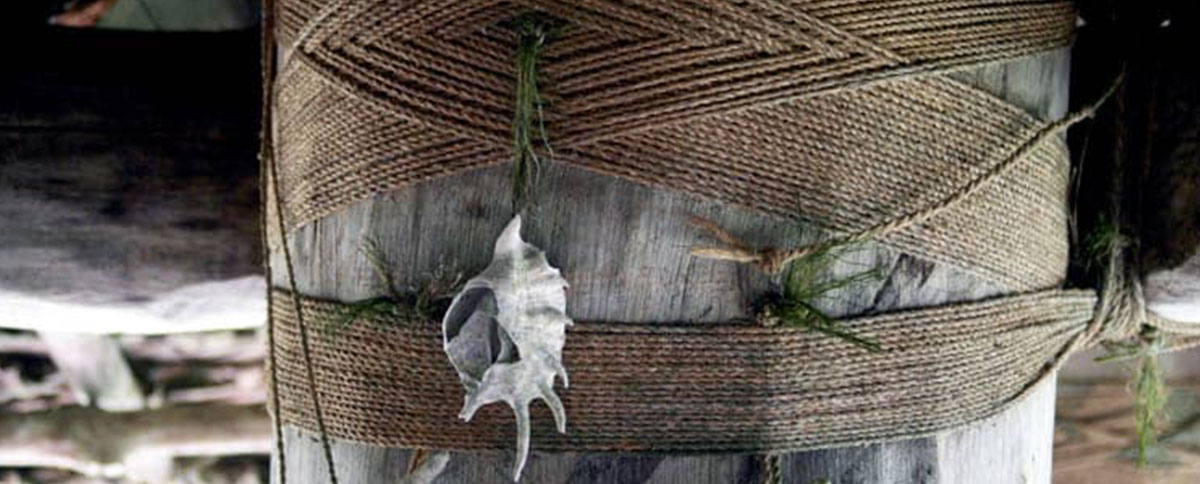

Among the sanctuaries in the MPAs is the Waloy community’s giant clam farm situated within a 151-acre marine area where these mammoth shells are protected from poachers to live longer lives, reproducing and repopulating their home.

The community of Tamil also has a giant clam farm under the auspices of the Tamil Resources Conservation Trust. Winner of the 2019 UN Equator Prize, TRCT was created in 2014 by the Tamil Council of Chiefs to “promote ridge-to-reef conservation for community and ecosystem reliance.”

Among the species found in the farms are the Bear Paw clam, also known as the Horse Hoof clam (Hippopus Hippopus), the Noah’s giant clam (Tridacna noae), and the Smooth giant clam (Tridacna derasa).

Depending on the species, they can live up to 100 years, grow up to four feet across, and weigh up to 500 pounds or more. Spending their entire lives adhered to one place in flat coral sand or broken coral, the clams serve as nurseries and refuges for fish and other marine life.

The exposed mantle, or soft tissue, of a giant clam exhibits a combination of bright colors and patterns caused by the algae in its system and may include yellow, green, iridescent blue or purple. Using a siphon to filter the water and consume the plankton that passes by, their diet also consists of the sugars and proteins produced by the algae. The algae, in turn, is rewarded with a safe home and access to sunlight for photosynthesis.

Among the rich oral history of Yap is the myth told by a local storyteller about how a giant lizard and a clam formed the island:

“In the very old days there was a giant lizard staying out in the sea. This lizard started eating people when they went out in the sea. People had a hard time traveling out in the sea. There was this boy, I forgot his name, who planned to kill this giant lizard. So, he made a canoe and took it out to the sea for testing. He went out and caught a fish, took it back home and put it on the fire, then sailed around the island and came back and the fish was overcooked and the fire was gone. He made another canoe and did the same thing, but this time the canoe was much faster than the first one. On the next day he went out to the sea and looked for the biggest clam. When he found one, he took it and put it on the canoe, then started looking for the giant lizard. Finally, he found the giant lizard. The boy made the lizard stick his head in the giant clam and the clam closed his mouth. The lizard tried to pull its head out but could not because the clam would not let loose of it. The lizard started swinging its tail and hit the island. First swing hit the north part of the island and cut, then with the second swing he hit the part in the south and cut and that was when it stopped because it did not have any power to swing for the third time. After that, the giant lizard died and everyone got happy because that young man made traveling easy out in the sea and to other islands nearby. When you look at the map you can see what I am talking about.”

It is said that giant clams can trap divers and kill them, but this is also a myth. The adductor muscles are used to close the shell, and, according to scientists, take too long to shut in defense of the intrusion while giving the diver who accidentally bumps into a clam enough time to pull away.

Visitors to Yap are invited to take a tour of Waloy’s Giant Clam Farm and snorkel among these gentle, colorful giants. It is prohibited to visit the area without a local guide so to arrange a tour, contact Manta Ray Bay Resort & Yap Divers at yapdivers@mantaray.com or call them at (691) 350-2300 or US toll free 800-348-3927 (800-DIVE-YAP). This article was first published at www.goworldtravel.com.