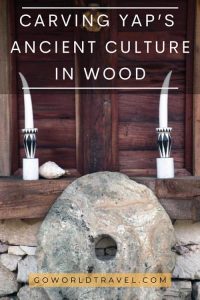

Carving Yap’s Ancient Culture in Wood

Once upon a time, the remote Micronesian island of Yap in the western Pacific Ocean had some of the finest woodcarvers in the world. Today, the art is being passed on by a handful of elders who still have the skill and knowledge.

But it’s feared that woodcarving is a dying art like so many others.

One of four states in the Federated States of Micronesia, the four large islands, seven small islands and 134 atolls that make up Yap are scattered across 100,000 square miles of the open ocean. Only 18 of them are inhabited by a total population of approximately 11,000.

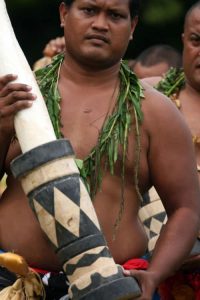

Today, Yap is considered one of the most intact cultures in the Pacific region. Wood carving provides a link in this place where culture and tradition are so important that Yap’s two traditional councils are written into the constitution as the fourth branch of government.

THE YAP CARVING COMMUNITY

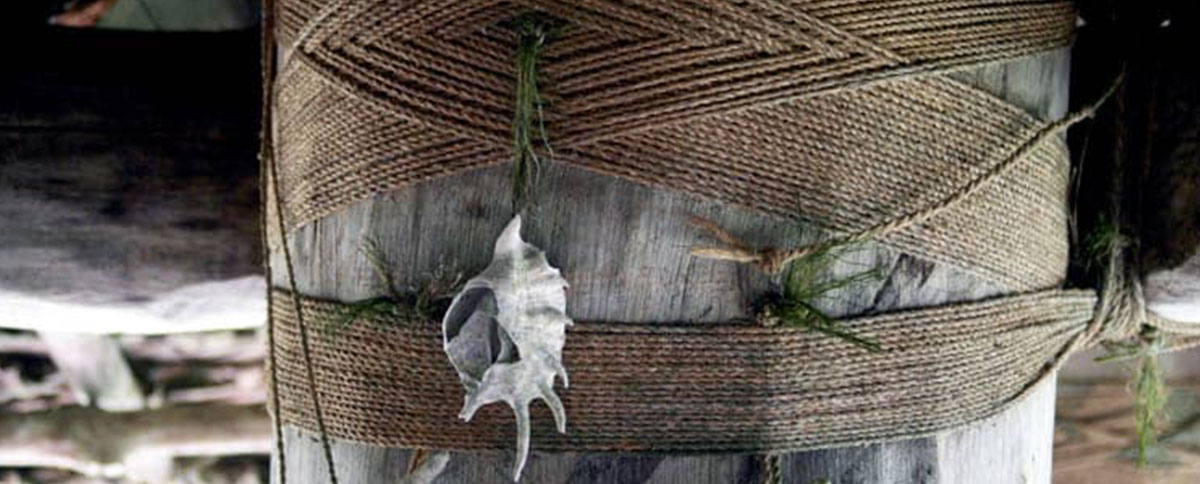

One of the most important meeting places for men in every community is the canoe house. This traditional structure made of wood, bamboo, dried palm fronds and coconut fiber rope is where boys as young as four or five begin to learn how to carve the single-outrigger canoes that have been used for centuries to ply the waters surrounding the far-flung islands.

They start with small pieces of wood, making birds and fish and other figures of nature for use as jewelry or for display on a wall or shelf. Working alongside the older boys who have progressed to more detailed projects, they watch and listen silently as the men carve the traditional sea-going vessels.

An adz is used to sculpt the wood. In days gone by, the handle of the adz was made of wood and the blade of sharpened clamshells or the giant clamshells that live in the waters surrounding the island. Today, the cutting edge is more commonly made of steel, but the handle is still often carved and smoothed by hand. The blades are sharpened with pieces of pumice.

Crafted in different sizes, the smaller adzes are used for cutting and carving handicrafts and personal and household items, while the larger ones are used for cutting trees and making sailing canoes. Beach mahogany, the hardest wood in the islands, and the breadfruit tree are the preferred woods.

In earlier days, the trees were carefully dug from the ground, rather than cut, to prevent fissures and ensure the strength of the wood. Today, trees that have fallen naturally are used more often to safeguard forest preservation and sustainability.

YAP MASTER CARVER

Master carver Michael Finey (@Arts-Of-Micronesia) uses scraps of wood or driftwood to help preserve the larger trees that are endangered on many of the islands throughout the Pacific. Finey is one of the few remaining Yapese woodcarvers. Now living in Saipan, he has won many awards for his work and made it his mission to keep the art alive through lecturing and teaching around the world.

It takes many years to become a master carver. One exquisite example of the art can be seen in the departure area at Yap International Airport. Created by the revered Yapese master carver, the late John Paul, the large, arcing, four-panel storyboard tells the story of the navigators who, more than 600 years ago, began sailing to the island of Palau 250 miles south of Yap.

CARVING YAP’S HISTORY

It was there that they discovered and began mining the aragonite stone that was carved into the heavy discs that are still in use today as one of the world’s most unique forms of currency aptly called “stone money.” The same basic principles of carving wood were used to form the donut-shaped wheels up to 12 feet in diameter that can be seen throughout Yap’s main island today.

The storyboard relates the tale of the men who began the treacherous journey across the open, shark-infested ocean, beginning with carving the canoes and embarking on the journey, to quarrying and carving the stone and finally towing the discs back to Yap on bamboo rafts tied to the backs of the canoes.

One panel shows lightning striking one of the canoes and a raging storm with men being tossed overboard. Many lost their lives. The value of stone money is not in its size but in the voyages and the perils along the way.

The final panel of the storyboard tells of the sailors’ triumphant return, welcomed by those they left behind, sometimes for months or even years, with the loud blow of the conch shell to announce their return. Two men tell the chief about their journey and a widow and child stand nearby being consoled by a fellow villager after hearing of the drowning of the woman’s husband during the voyage.