Andy and Allison Vitsky Sallmon in Yap

Exhilarated and starving, we pulled off our gear as the divemaster began the roll call. With all passengers accounted for, the boat captain started the motor and headed toward the resort, where lunch awaited our group of hungry divers. We boisterously compared notes on the morning’s incredible manta interactions. At least a dozen of the graceful rays had closely circled us, mugging for our cameras like supermodels.

The boat suddenly slowed. The divemaster was pointing at a disturbance on the water’s surface. Seconds later, the surface was pierced by a tall, straight dorsal fin. This was no porpoise. Seconds later, shouts rang out. Read more…

“Orcas?”

“Yeah! Orcas!”

Exhilarated and starving, we pulled off our gear as the divemaster began the roll call. With all passengers accounted for, the boat captain started the motor and headed toward the resort, where lunch awaited our group of hungry divers. We boisterously compared notes on the morning’s incredible manta interactions. At least a dozen of the graceful rays had closely circled us, mugging for our cameras like supermodels.

The boat suddenly slowed. The divemaster was pointing at a disturbance on the water’s surface. Seconds later, the surface was pierced by a tall, straight dorsal fin. This was no porpoise. Seconds later, shouts rang out. Read more…

“Orcas?”

“Yeah! Orcas!”

Incredibly, we had stumbled across a pod of four orcas. After some initial hesitation about getting in the water (“Is this safe? They’re called ‘killer whales,’ right?”), lunch was forgotten, and we scrambled to don masks, fins and snorkels.

The captain maneuvered the boat to allow us to slip into the path of the orcas again and again, but despite our efforts we never got close enough to the whales to take any unforgettable images.

Dolefully, we headed back toward the ladder, only to notice a large, shiny disc lying flat on the water’s surface. We slowly approached it, ultimately recognizing the bizarre creature as a massive Pacific sunfish.

This was getting a little ridiculous. I sputtered to the surface, spit out my snorkel and started yelling.

“Mola!”

Unlike the pod of orcas, the surprised mola stayed nearby for a few precious minutes, providing all of us some prime photo opportunities before it swam away.

Back on the boat, eight pairs of eyes carefully surveyed the ocean for any other unusual marine life. (I had my hopes pinned on a basking shark.) However, the hushed concentration was loudly interrupted by someone’s stomach growling in angry protest at the prolonged snorkeling session. Evidently, it was now truly time for lunch. We headed home at last, delighted with our fantastic luck.

Incredibly, we had stumbled across a pod of four orcas. After some initial hesitation about getting in the water (“Is this safe? They’re called ‘killer whales,’ right?”), lunch was forgotten, and we scrambled to don masks, fins and snorkels.

The captain maneuvered the boat to allow us to slip into the path of the orcas again and again, but despite our efforts we never got close enough to the whales to take any unforgettable images.

Dolefully, we headed back toward the ladder, only to notice a large, shiny disc lying flat on the water’s surface. We slowly approached it, ultimately recognizing the bizarre creature as a massive Pacific sunfish.

This was getting a little ridiculous. I sputtered to the surface, spit out my snorkel and started yelling.

“Mola!”

Unlike the pod of orcas, the surprised mola stayed nearby for a few precious minutes, providing all of us some prime photo opportunities before it swam away.

Back on the boat, eight pairs of eyes carefully surveyed the ocean for any other unusual marine life. (I had my hopes pinned on a basking shark.) However, the hushed concentration was loudly interrupted by someone’s stomach growling in angry protest at the prolonged snorkeling session. Evidently, it was now truly time for lunch. We headed home at last, delighted with our fantastic luck.

While the events recounted above are absolutely true, that day was admittedly quite exceptional. We’ve heard of people seeing all manner of large marine life here, though. And remarkably, the manta interaction described at the outset of our tale is extremely typical of a dive day in Yap.

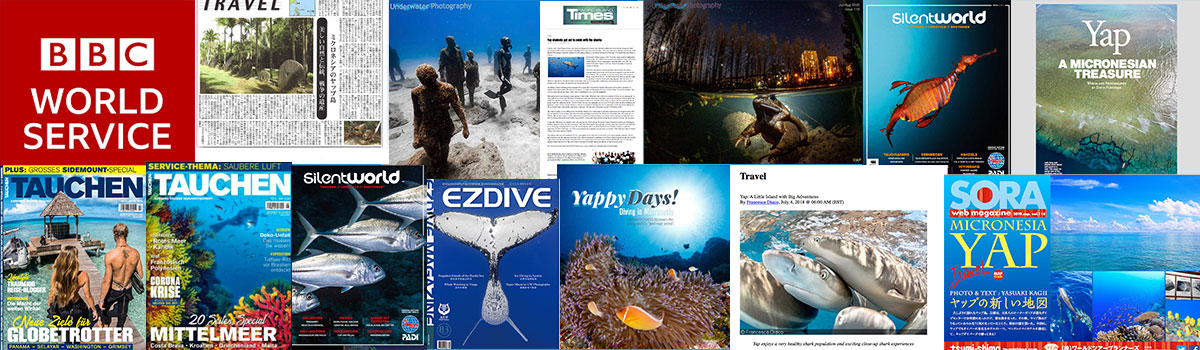

Yap Island is one of the best places in the world to view manta rays, which is evidenced by the large number of divers who travel here year after year. Mantas are protected throughout the region, inhabiting a sanctuary that encompasses more than 8,200 square miles. It’s no wonder there are more than 100 unique mantas here, and new animals are identified each year.

Yap’s thriving manta ray population is not a recent development, but it was not always so warmly received. Yapese fishermen were once wary of the creatures they called “devilfish,” using tales of the fearsome animals to discourage their children from misbehaving.

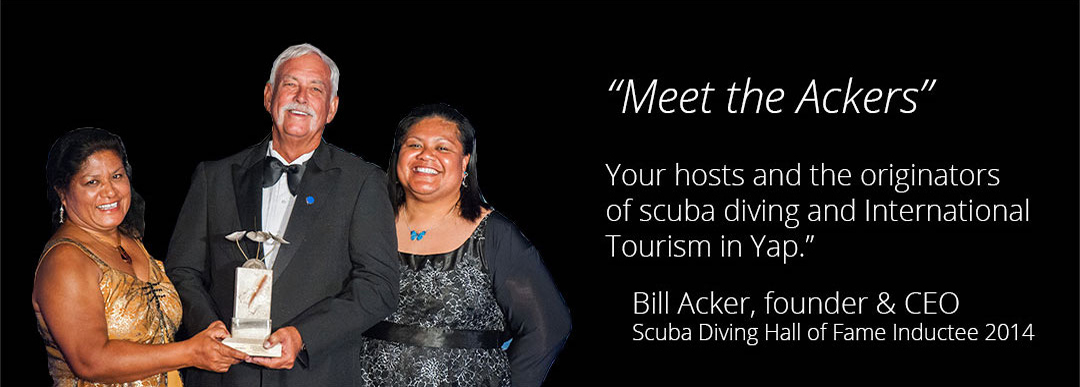

This was the prevalent mindset as recently as 1976, when Peace Corps volunteer Bill Acker was sent to Yap for a two-year assignment. Acker quickly became enamored of scuba diving, noting the large, inquisitive rays that aggregated in some of the current-swept channels. They were so common, in fact, that Acker assumed mantas were rather an ordinary sight everywhere. When he decided to relocate to the islands permanently to establish Yap’s first scuba operation, Yap Divers, he therefore downplayed the mantas to visitors. Acker preferred to take clients to the more remote outer reefs, where the currents were milder and the visibility was better.

This changed in 1986, when the publisher of Skin Diver Magazine, Paul Tzimoulis, visited Yap. Tzimoulis’ trip coincided with ghastly weather that made a visit to the outer reefs impossible. His consolation dive (imagine that) was the now-famous Mi’L Channel, where he found himself face-to-face with Yap’s legendary devilfish. Shortly thereafter, the magazine classified the site as one of the best in the world. We’re guessing the resulting influx of manta-mad scuba divers did wonders to improve the local reputation of the rays.

While the events recounted above are absolutely true, that day was admittedly quite exceptional. We’ve heard of people seeing all manner of large marine life here, though. And remarkably, the manta interaction described at the outset of our tale is extremely typical of a dive day in Yap.

Yap Island is one of the best places in the world to view manta rays, which is evidenced by the large number of divers who travel here year after year. Mantas are protected throughout the region, inhabiting a sanctuary that encompasses more than 8,200 square miles. It’s no wonder there are more than 100 unique mantas here, and new animals are identified each year.

Yap’s thriving manta ray population is not a recent development, but it was not always so warmly received. Yapese fishermen were once wary of the creatures they called “devilfish,” using tales of the fearsome animals to discourage their children from misbehaving.

This was the prevalent mindset as recently as 1976, when Peace Corps volunteer Bill Acker was sent to Yap for a two-year assignment. Acker quickly became enamored of scuba diving, noting the large, inquisitive rays that aggregated in some of the current-swept channels. They were so common, in fact, that Acker assumed mantas were rather an ordinary sight everywhere. When he decided to relocate to the islands permanently to establish Yap’s first scuba operation, Yap Divers, he therefore downplayed the mantas to visitors. Acker preferred to take clients to the more remote outer reefs, where the currents were milder and the visibility was better.

This changed in 1986, when the publisher of Skin Diver Magazine, Paul Tzimoulis, visited Yap. Tzimoulis’ trip coincided with ghastly weather that made a visit to the outer reefs impossible. His consolation dive (imagine that) was the now-famous Mi’L Channel, where he found himself face-to-face with Yap’s legendary devilfish. Shortly thereafter, the magazine classified the site as one of the best in the world. We’re guessing the resulting influx of manta-mad scuba divers did wonders to improve the local reputation of the rays.

The cleaning stations located in Mi’L Channel and Goofnuw Channel are best known for thrilling manta interactions, but eagle rays, reef sharks, turtles and barracudas can be spotted there, too. At first glance these sites can be a bit of a letdown, but don’t be fooled. Divers often descend in a brisk current and grope their way to a pile of unremarkable rubble where they hold on for dear life. Then they wait, staring into the blue, willing the rays to appear. And mantas nearly always do appear, circling patiently while waiting to be cleaned by small groups of skilled wrasses. In a single moment, an uninspiring dive site can be transformed as divers experience close passes by manta after manta. Photographers may find themselves having to back up to fit the entire ray in the frame — they approach that closely.

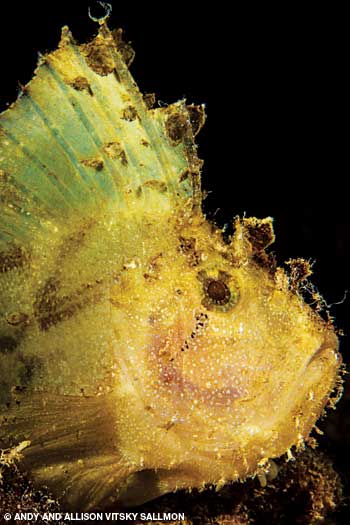

On the rare days that manta numbers are disappointing, don’t despair: The channels are not all rubble and sand. They also contain lovely hard-coral outcroppings swarmed by anthias and glassfish, and inspection of the walls may reveal hunting octopuses, leaf scorpionfish and branches of purple soft coral. While these channels are the sites most often visited for manta viewing, the large indigenous population of the creatures means they are a common spectacle at any of Yap’s dive sites.

More Than Mantas

The cleaning stations located in Mi’L Channel and Goofnuw Channel are best known for thrilling manta interactions, but eagle rays, reef sharks, turtles and barracudas can be spotted there, too. At first glance these sites can be a bit of a letdown, but don’t be fooled. Divers often descend in a brisk current and grope their way to a pile of unremarkable rubble where they hold on for dear life. Then they wait, staring into the blue, willing the rays to appear. And mantas nearly always do appear, circling patiently while waiting to be cleaned by small groups of skilled wrasses. In a single moment, an uninspiring dive site can be transformed as divers experience close passes by manta after manta. Photographers may find themselves having to back up to fit the entire ray in the frame — they approach that closely.

On the rare days that manta numbers are disappointing, don’t despair: The channels are not all rubble and sand. They also contain lovely hard-coral outcroppings swarmed by anthias and glassfish, and inspection of the walls may reveal hunting octopuses, leaf scorpionfish and branches of purple soft coral. While these channels are the sites most often visited for manta viewing, the large indigenous population of the creatures means they are a common spectacle at any of Yap’s dive sites.

More Than Mantas

The manta encounters are Yap’s most publicized underwater feature, a fact that has been both a blessing and a curse. Many divers visit, but once they have seen the rays, they believe they have seen all the destination has to offer. As a result, Yap welcomes a constant flow of visitors “stopping over” for a few days en route to other Pacific destinations. The injustice of this practice becomes glaringly clear to those who settle in for a longer stay.

One group of less-promoted residents has distracted us from mantas repeatedly: sharks. Vertigo is an exceptional shark dive that eclipses the individual encounters commonly experienced at other sites. The site consists of a pretty hard-coral wall laden with crinoids and small sponges, but the introduction of a simple PVC tube filled with bait amplifies the thrill value significantly. Minutes after the bait is submerged, the site swarms with dozens of bold gray reef sharks and an occasional blacktip thrown in for variety. This is already the most adrenaline-charged dive in Yap, and if current efforts to ban shark fishing throughout Micronesia succeed, it will only intensify.

The manta encounters are Yap’s most publicized underwater feature, a fact that has been both a blessing and a curse. Many divers visit, but once they have seen the rays, they believe they have seen all the destination has to offer. As a result, Yap welcomes a constant flow of visitors “stopping over” for a few days en route to other Pacific destinations. The injustice of this practice becomes glaringly clear to those who settle in for a longer stay.

One group of less-promoted residents has distracted us from mantas repeatedly: sharks. Vertigo is an exceptional shark dive that eclipses the individual encounters commonly experienced at other sites. The site consists of a pretty hard-coral wall laden with crinoids and small sponges, but the introduction of a simple PVC tube filled with bait amplifies the thrill value significantly. Minutes after the bait is submerged, the site swarms with dozens of bold gray reef sharks and an occasional blacktip thrown in for variety. This is already the most adrenaline-charged dive in Yap, and if current efforts to ban shark fishing throughout Micronesia succeed, it will only intensify.

After giant manta rays and a writhing mass of reef sharks, what more could two photographers ask for? Certainly, we’d be perfectly satisfied to alternate mantas and sharks, day in and day out for weeks on end. However, with local diving pioneer Bill Acker himself repeatedly extolling the loveliness of Yap’s other dive sites, we finally decided to forego the big-animal experiences for a day. A single day blurred into many as we became acquainted with Yap’s lovely and diverse reefs. One standout was Cabbage Patch, a series of undulating, steeply sloping walls richly encrusted with delicate lettuce coral. The reef is inhabited by anemones, crinoids and tube worms, and large turtles are often found feeding along the top of the reef in this area.

Our hands-down favorite reef is Yap Caverns. Located at the extreme southwestern tip of Yap Island, this site is composed of a series of hard-coral pinnacles that enclose a maze of caverns and swim-throughs. Within the main cavern, a school of resident glassfish sweeps back and forth while stingrays and white-tip reef sharks tuck into the corners to nap. Peering back toward the cavern entrance may yield the most incredible vista of all: We’ve seen whale sharks, mantas and eagle rays pass by the pinnacles. In fact, we’ve heard that just about anything can be seen at this part of the island, including pilot whales and the occasional pod of dolphins. Divers who prefer looking for small creatures will also enjoy this site; we have photographed leaf scorpionfish, nudibranchs, shrimp and crabs hidden among the reef’s gorgonians and whip corals.

After giant manta rays and a writhing mass of reef sharks, what more could two photographers ask for? Certainly, we’d be perfectly satisfied to alternate mantas and sharks, day in and day out for weeks on end. However, with local diving pioneer Bill Acker himself repeatedly extolling the loveliness of Yap’s other dive sites, we finally decided to forego the big-animal experiences for a day. A single day blurred into many as we became acquainted with Yap’s lovely and diverse reefs. One standout was Cabbage Patch, a series of undulating, steeply sloping walls richly encrusted with delicate lettuce coral. The reef is inhabited by anemones, crinoids and tube worms, and large turtles are often found feeding along the top of the reef in this area.

Our hands-down favorite reef is Yap Caverns. Located at the extreme southwestern tip of Yap Island, this site is composed of a series of hard-coral pinnacles that enclose a maze of caverns and swim-throughs. Within the main cavern, a school of resident glassfish sweeps back and forth while stingrays and white-tip reef sharks tuck into the corners to nap. Peering back toward the cavern entrance may yield the most incredible vista of all: We’ve seen whale sharks, mantas and eagle rays pass by the pinnacles. In fact, we’ve heard that just about anything can be seen at this part of the island, including pilot whales and the occasional pod of dolphins. Divers who prefer looking for small creatures will also enjoy this site; we have photographed leaf scorpionfish, nudibranchs, shrimp and crabs hidden among the reef’s gorgonians and whip corals.

Given Yap’s renowned manta population, there are not many divers who travel here dreaming of nudibranchs. However, gusty afternoon winds make manta, shark and outer-reef dives uncommon post-lunch events, so keen divers are often taken to the protected inner reefs. One good option is Slow ‘n Easy, a gentle sand slope punctuated by hard-coral bommies. Sandy areas hold an abundance of pipefish, garden eels and symbiotic shrimp/goby pairs, as well as occasional mantis shrimp and stonefish. Inspection of the reef structure reveals nudibranchs, blennies, leaf scorpionfish and whip coral shrimp. Shore dives also yield unexpected finds: The murky waters near the resort docks are great places to look for nudibranchs and small jellyfish.

Given Yap’s renowned manta population, there are not many divers who travel here dreaming of nudibranchs. However, gusty afternoon winds make manta, shark and outer-reef dives uncommon post-lunch events, so keen divers are often taken to the protected inner reefs. One good option is Slow ‘n Easy, a gentle sand slope punctuated by hard-coral bommies. Sandy areas hold an abundance of pipefish, garden eels and symbiotic shrimp/goby pairs, as well as occasional mantis shrimp and stonefish. Inspection of the reef structure reveals nudibranchs, blennies, leaf scorpionfish and whip coral shrimp. Shore dives also yield unexpected finds: The murky waters near the resort docks are great places to look for nudibranchs and small jellyfish.

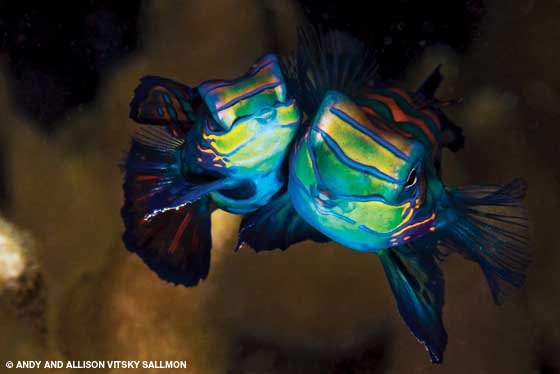

As sunset approaches, we always find ourselves eager to dive again. That’s because Yap offers one of the best mandarinfish dives we’ve experienced anywhere. Rainbow Reef, a large clump of mucky staghorn coral surrounded by a sand patch, is located mere minutes from resort docks. Divers gather here at dusk to view the colorful fish courting and (we hope) pairing off to rise gracefully into the water column in a fascinating, photogenic mating ritual. Even if the mandarinfish are not feeling amorous, this site harbors other interesting creatures, such as cuttlefish, pipefish, eels and scorpionfish.

As our most recent visit drew to an end, we sat at the end of the dock comparing mandarinfish images while the moon rose over the mangroves. Another couple passed by us, discussing strategies to extend their stay, and we looked at one another knowingly. Destinations everywhere become notorious for a single exceptional feature and are promptly pigeonholed accordingly, and in Yap’s case, the manta rays are that exceptional attribute. However, after several visits to this Micronesian paradise, we have learned firsthand that these giant rays are only a small part of what Yap has to offer.

As sunset approaches, we always find ourselves eager to dive again. That’s because Yap offers one of the best mandarinfish dives we’ve experienced anywhere. Rainbow Reef, a large clump of mucky staghorn coral surrounded by a sand patch, is located mere minutes from resort docks. Divers gather here at dusk to view the colorful fish courting and (we hope) pairing off to rise gracefully into the water column in a fascinating, photogenic mating ritual. Even if the mandarinfish are not feeling amorous, this site harbors other interesting creatures, such as cuttlefish, pipefish, eels and scorpionfish.

As our most recent visit drew to an end, we sat at the end of the dock comparing mandarinfish images while the moon rose over the mangroves. Another couple passed by us, discussing strategies to extend their stay, and we looked at one another knowingly. Destinations everywhere become notorious for a single exceptional feature and are promptly pigeonholed accordingly, and in Yap’s case, the manta rays are that exceptional attribute. However, after several visits to this Micronesian paradise, we have learned firsthand that these giant rays are only a small part of what Yap has to offer.

Yap has been nicknamed “the land of stone money,” a moniker that references its carved rock currency. Ancient Yapese traveled approximately 300 miles to neighboring Palau to mine the stone from which the money was carved. The coins, called rai, could be up to 14 feet in diameter, so canoe transport back to Yap was an extremely hazardous proposition.

The value of the currency depended on many factors, including size and shape, quality and — most important — danger faced during acquisition. While the coins are still used in certain transactions, such as real estate purchases and bridal dowries, their size means they are not commonly moved, even when ownership changes. Rather, rai is generally kept in village “banks,” where it is easily viewable by visitors.

The continued custom of rai exchange provides a glimpse into the local mindset; the Yapese have maintained many rich traditions that remain minimally influenced by the outside world. Village visits offer a glimpse into a culture that seems to be pulled directly from a motion picture. Bare-breasted women clad only in flower necklaces and grass skirts practice weaving and dance, while men demonstrate their prowess at fishing and betelnut harvest.

Diving Yap

Yap Island is the hub of Yap State, a cluster of more than 100 islands and atolls within the Federated States of Micronesia. The capital city, Colonia, is located here, as is the international airport. Yap Island is the primary destination for divers and nondivers alike. The primary language is English, and the currency is the U.S. dollar.

The diving here is excellent year-round, though the winds are calmest from June through October (which may permit access to a wider array of sites). Nearly all diving is done by boat, since the channels and outer reefs are not accessible from shore. Water temperature averages 82°F. There is a recompression chamber on Yap Island.

Yap has been nicknamed “the land of stone money,” a moniker that references its carved rock currency. Ancient Yapese traveled approximately 300 miles to neighboring Palau to mine the stone from which the money was carved. The coins, called rai, could be up to 14 feet in diameter, so canoe transport back to Yap was an extremely hazardous proposition.

The value of the currency depended on many factors, including size and shape, quality and — most important — danger faced during acquisition. While the coins are still used in certain transactions, such as real estate purchases and bridal dowries, their size means they are not commonly moved, even when ownership changes. Rather, rai is generally kept in village “banks,” where it is easily viewable by visitors.

The continued custom of rai exchange provides a glimpse into the local mindset; the Yapese have maintained many rich traditions that remain minimally influenced by the outside world. Village visits offer a glimpse into a culture that seems to be pulled directly from a motion picture. Bare-breasted women clad only in flower necklaces and grass skirts practice weaving and dance, while men demonstrate their prowess at fishing and betelnut harvest.

Diving Yap

Yap Island is the hub of Yap State, a cluster of more than 100 islands and atolls within the Federated States of Micronesia. The capital city, Colonia, is located here, as is the international airport. Yap Island is the primary destination for divers and nondivers alike. The primary language is English, and the currency is the U.S. dollar.

The diving here is excellent year-round, though the winds are calmest from June through October (which may permit access to a wider array of sites). Nearly all diving is done by boat, since the channels and outer reefs are not accessible from shore. Water temperature averages 82°F. There is a recompression chamber on Yap Island.

Original Article on Alert Diver.com

What others say

Great article Andy and Allison. Thanks to you I`ve seen some fish that I don’t if they do really exist.. I’m saving your pics for my laptop wallpaper. Clusters Beowulf